Sleep comes to most of us so easy that we rarely ever, if at all, spare it a thought. A bed’s always been within reach, a roof always above the head. What’s the big deal, really?

So imagine my confusion when I was recently told about a documentary film based on the ‘sleep mafia’ in Delhi. The concept sounded absurd right from the word go and a 74-minute documentary about ‘sleep’ sounded like a film that would put me to…well, sleep. Suffice it to say, then, that when I finally saw the trailer to the film sometime later, my mouth remained open for longer than is considered appropriate.

Through a series of happy coincidences, I was asked if I’d be willing to watch an early cut of the film and review it. And here I am, inspired enough to do a thousand word article on the film, which is really something, since not much inspires me otherwise.

A sleep shelter in Old Delhi.

Cities of Sleep, filmmaker Shaunak Sen’s first feature documentary, was shot in Delhi by a motley crew of three, mostly during the unforgiving winter of 2013. Produced by the Films Division of India, the film follows the lives of Shakeel, a migrant from Assam who the official synopsis describes as a ‘renegade homeless sleeper’ and Ranjeet, the owner of what is termed a sleep-cinema shelter, a thin piece of land under the Yamuna bridge that houses a makeshift cinema room that doubles up as a sleep shelter at night. Shakeel has, over the last 7 years, slept in a diverse range of spots like the footpath, bus stands, parking lots, park benches and illegally-occupied spaces provided by sleep mafia at nominal prices, run by a man who goes by the name of Jamaal bhai in Old Delhi. Ranjeet, on the other hand, has been making a living out of his shelter under Delhi’s oldest bridge, a popular spot for the homeless because of cold breeze the Yamuna is accompanied by. While these characters come from different places, geographically and otherwise, what ties them together are their struggles with sleep. And when I say sleep, I don’t just mean the simple act of dozing off, but the social, philosophical and economical implications of it all.

A couple of minutes into the film I realised that my initial reaction to the film’s idea arose not out of the absurdity of the very concept, but out of my own ignorance. Its a realisation that most viewers will experience when they watch the film for the first time, considering how oblivious we sometimes are to what happens around us, in our own city. I, for one, have lived in Delhi for 22 years now and I never remember seeing Connaught Place as empty and silent as it is shown in the first few seconds of the film. And neither have I witnessed anything even remotely close to the chaos that unfolds soon after these few seconds have passed.

Meena Bazaar, an old market Shakeel spends most of his nights in.

For a film based on two characters who belong to a low-income background, one of the biggest challenges, I’m assuming, is to not simply be termed as a film on ‘poverty’. It’s a genuine obstacle most documentary filmmakers face, owing to the various preconceived notions we’ve come to associate with documentary films based in India, or for that matter, any developing nation. And yet, Shaunak and his crew seem to have developed a certain understanding with their subjects in a way that the film doesn’t end up looking exploitative or intrusive, but instead takes the ‘silent observer’ route. The filmmaker’s physical presence in the film is negligible and aptly so, since the circumstances he’s shooting in don’t require constant prodding or interference. In fact, a number of times in the film, drama just happens to unfold in front of the camera of it’s own accord.

A particularly dramatic sequence when a major storm hits the city, drenching Jamaal bhai’s sleep shelter and almost uprooting his stall is, in a manner of speaking, extremely cinematic to watch but not in a way that would seem contrived in a documentary. Instead, for a film based on a concept as seemingly simple and two-dimensional as sleep, the chaos that does ensue feels like an organic reaction to the circumstances the subjects are a part of, and not ‘staged misery’ meant to win the sympathy of the upper class viewer.

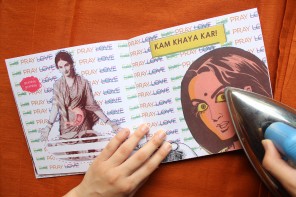

A thin strip of land under the Yamuna bridge doubles up as a sleep shelter as well as a makeshift cinema for the homeless.

In fact, in one of the film’s most telling moments, Shakeel, after having walked around for hours looking for a place to sleep, finally ends up at a bus stop and before dozing off, disappointedly accuses the filmmaker of not helping him, in spite of being perfectly capable to. The inclusion of this scene in the film is a rare acknowledgement of the obvious class difference and the resulting power equation between the documentary filmmaker and his subject, and it’s nice to see the filmmaker not wanting to pretend otherwise. A camera in your hand grants you a certain authority, especially when dealing with a subject belonging to a lower strata of society and while most filmmakers are quick to take advantage of that power, rarely do they own up to the responsibility that comes with it (no, I’m not quoting Spiderman). So it’s refreshing to see Shaunak turn the lens towards himself and momentarily put the very art of making an unobtrusive documentary under scrutiny.

And that, I think, is the film’s biggest victory. In unabashedly letting circumstances take their own course and not pretending to be something that it isn’t, the film taps into the immense potential reality holds. While the filmmaker no doubt empathises with the subjects, the film itself isn’t intended to be used as a vehicle for change. It comes as no surprise, then, that the story, much like reality itself, denies its viewer a didactic, conclusive ending with a social message at the end. And by the time we’re watching the last frame of the film, we find ourselves back where we first started, even though in actuality so much has changed since.

Cities of Sleep, currently in its final post-production stage, is intended for release soon. Watch its trailer here.